Chapter 8 — Oborea in Iberia

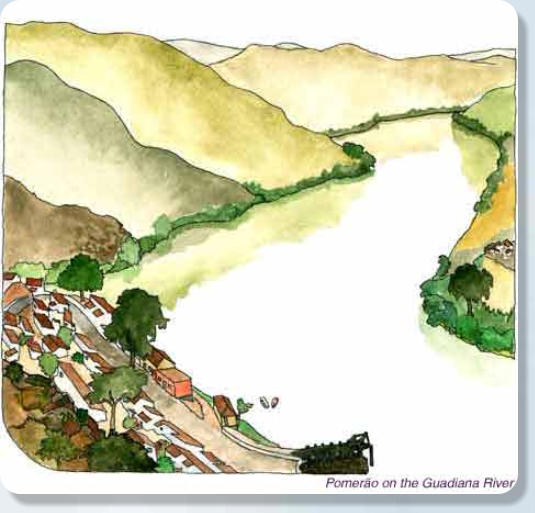

The eight hundred mile passage from the Azores to Portugal was slow. For a week we were under the influence of the Azores high with light winds and calm seas. Saw several ships including a Greek freighter that changed course to pass close alongside and give her paying passengers a thrill. The last hundred miles to Cape St Vincent was a bit of a worry because half the shipping lanes in the world seem to converge here: all the traffic between the Mediterranean and North America and northern Europe, as well as tankers heading from the Persian Gulf to Europe around the Cape of Good hope. It was at this point, of course, that the "Portuguese Trades" started to blow with a vengeance; hard from the north. I had to reduce sail to double reefed main and mizzen with small jib as I beam reached through twelve foot seas at night. In the troughs my range of vision was about two hundred feet, while on the crests I could see the masthead lights of big ships all around me. Miraculously none came closer than three miles and I steered right through the middle of them arriving off Cape St Vincent, the south west corner of Iberia, at daybreak. As the sun rose I pulled into Sagres Bay, just past the cape, and dropped anchor in European waters for the first time, then fell into my bunk for a much needed sleep. I woke in mid afternoon and looked around. What a contrast to the Azores; low brown and orange cliffs and, at the head of the bay, a small beach with a couple of bars. Behind the beach lay a parched dry landscape with a few prickly shrubs. On the cliff to the west was the ruin of an ancient fortress baked to the same colour as the landscape. I stayed the night in Sagres Bay and then headed east to Faro, my intended port of entry. This was a spinnaker run at about two knots for fifty miles along the Algarve, the playground coast of Portugal and still the best holiday bargain in Europe. The coast I was following consisted of low cliffs alternating with beautiful white sand beaches. The resort towns looked much like those of Florida from the offing with high rise hotels and condos. Closer observation through the binoculars revealed a major difference on the beaches though: an almost total absence of covered bosoms. Ten miles before Faro the coastline changed to low barrier dunes along the sea and behind them salt marshes and tidal creeks. Faro itself is five miles up a river, where the marsh changes to fast land. It is the main supply base for the Algarve and looks much like any modern city with its high buildings until you get close enough to see the lovely old walled section of town. With Oborea safely anchored in the marshes I dinghied ashore to find the stores full of bargains, and the sidewalk cafes full of pale British tourists and earnest German back-packers with, of course, a sprinkling of Australians. After stocking my larder and getting a haircut (with full commentary in Portuguese) I sailed down the river to Culatra, a small fishing village of about a hundred homes built right on the barrier dunes. The only vehicles were a couple of farm tractors; all communication was by water. A half mile across the dunes was a lovely ocean beach, many miles long and almost deserted. At Culatra I put Oborea on the sand for a clean up. With six foot tides I had lots of time to scrub the bottom and touch up the antifouling. While waiting for the sea to return I dug cockles for dinner. I spent a week in these tidal creeks, taking the ferry into the big fishing port of Olhão as necessary for supplies, before sailing east along the coast to the Guadiana river, the border between Spain and Portugal. This is a good time to mention the paperwork involved in taking a yacht through Portuguese waters. At Horta I had been issued a cruising permit which I had to have stamped by the Port Captain, the health authorities and the police. These had to stamp again before I left, and at each subsequent Portuguese port I had to get a stamp from the Capitain do Porto and the Guarda Fiscal upon arrival and again on leaving. This was all done with great politeness and without charge, and Oborea's vital statistics are now entered by hand in dusty ledgers in nine Portuguese ports. At Vila Real do San Antonio, at the mouth of the Guadiana River I had to get an additional stamp from customs as this is a border town. I also had to get a special additional cruising permit to go up the Guadiana. I sailed twenty four miles up the river, away from all of the tourist glitter of the Algarve and into an area of rolling arid hills that closed in on the river as we got further from the sea. Riding the strong tides, I anchored the first night at Alcoutim, and the next day went on to Pomerão. The river is deep all the way up, and copper ore was once loaded here into coastal freighters, but it has been a few years since there has been any commercial shipping here. Today the little village sleeps in the hot dry hills. The police post (even here they have rubber stamps) was a little cottage with a grape vine growing over the doorway. In the biggest room the official desk and the official motorbike shared equal space. The ferry across the river was an elderly gentleman with a large moustache and a small rowing boat. I spent a week in the peace of the upper Guadiana. Herons fished and European kingfishers flew from branch to branch like tiny brilliant emeralds. I took long walks into the hills where I came upon tiny villages that looked like bible story illustrations; low mud-coloured houses with tiled roofs, clinging to sun-baked hillsides. Around the villages goatherds tended their flocks. As I left Pomerão it was too quiet to start the motor, and so I drifted off with the tide, catching occasional puffs of wind between the hills. Once, while I was below for a moment putting the kettle on for tea, Oborea drifted gently into a pomegranate tree; I picked half a dozen ripe fruit before pushing off again. Reaching the sea, I sailed twenty miles back to Faro to pick up mail and supplies for it was time to leave Europe and start heading homeward. I had found the attitude to yachts in the Algarve quite different from the enthusiastic welcome extended in the Azores. Here they were largely ignored, a sort of "don't bother us and we won't bother you" attitude from the authorities. Apart from at a large crowded and expensive marina at Vilamoura, yachts usually share space with the fishing boats and rafting up is a way of life. In fact with the large tidal range and generally not very clean walls in the fishing harbours, there was competition not to be the boat next to the wall. Sometimes I saw boats rafted five or six deep while there were still empty spaces alongside! Europeans take it all in their stride, always observing a sort of etiquette: cross the other boat in your bare feet and always forward of the mast, never through the cockpit. I was often surprised at how easily a boat in the centre of the raft could slip out and be on its way with the minimum of disturbance.