Chapter 9 — Some More Eastern Atlantic Islands

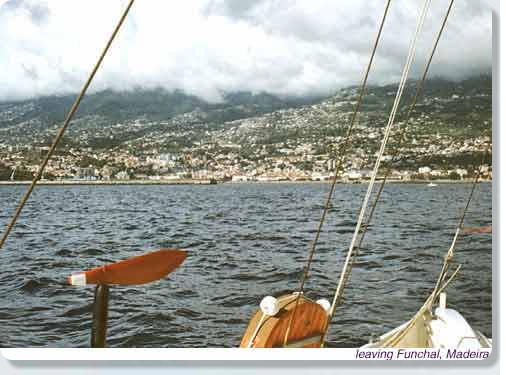

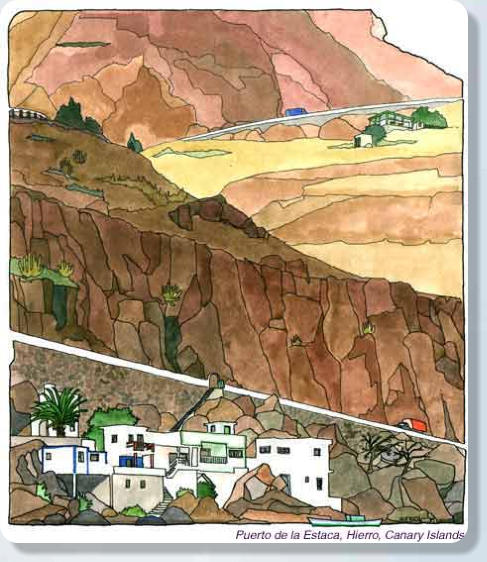

I left Portugal for the 500 mile trip to Madeira in early October, riding down the river from Faro on the afternoon tide. Outside Cabo Santa Maria I found light headwinds and started tacking south-west. By next morning I had cleared the wind-shadow of the Portuguese mainland and started making good progress under the strong northerly "Portuguese Trades". That morning about an hour after sunrise I saw a cargo ship ahead heading east for Gibraltar. It looked as if we would pass safely green to green, but in these cases I usually give the other ship a call on the VHF just to make sure he has seen me. In this case the other ship came back to thank me for calling because I was right in the sun-path and almost impossible to see. A good point to remember when the sun is low in the sky. Winds continued out of the northern quadrant for the next couple of days, and one day I saw a distant whale. At about two in the morning on the third day I picked up the loom of the light at the east end of Porto Santo, the most northerly of the Madeira Archipelago, and I started to predict a mid-morning arrival. I should have known better; the wind went ahead and it started to rain and it was mid-afternoon before I dropped the hook. Even then I was not left in peace. In common with all the other eastern Atlantic islands there are no natural harbours on Porto Santo. The normal anchorage is off the beach in front of the town, but with the wind continuing to back I headed for the protection of the artificial commercial harbour a mile to the east. This harbour was quite large and practically empty so I just anchored in a quiet out of the way corner. It seems this is not allowed and I had to tie up in the small and definitely B grade marina which charged four times the rate of the beautiful down-town marina in Horta. This put me off a bit and I did not stay long on the island. Ashore the white-washed tile roofed houses were similar to other Portuguese towns I had visited, but the flatter pitch of the roofs and the palm trees gave the place a tropical feel. The island is volcanic with a number of steep little peaks and cliffs of lava rock. Visitors come over for the day on the ferry from Madeira to use the beautiful beach and there are a number of small hotels and a campsite. After two days I sailed thirty miles to Madeira where I encountered the most spectacular scenery I had seen to date. The island is high and monolithic like the Azores, but from seaward seemed much more densely populated with houses clinging to the slopes everywhere. The mountains were intersected with steep, narrow ravines which made for some pretty hair-raising highway construction. I could look up from the deck and see trucks and buses driving by a notch in the cliffs high above me. The large city of Funchal is set in a natural amphitheatre about three miles across and climbing to almost three thousand feet at the rim. That first night I sat on deck drinking my evening tea and gazing in awe at the lights of the city and suburbs climbing high into the sky until they joined the stars. Three quarters of the way up a twin-towered church outlined in light bulbs looked like a tiny Christmas tree ornament suspended in the velvet sky. Madeira has been a destination for European tourists for about two hundred years. The down town area has wide jacaranda shaded avenues and big old parks with swans swimming in the pools. Travelling inland the roads become steeper and steeper—the sidewalks are often steps, and in one area they still slide tourists down the cobbled streets on wood and wicker sleds accompanied by two attendants in eighteenth century sailor costume and a strong smell of burning. There is a small crowded marina in downtown Funchal, but yachts are also permitted to anchor in the north east corner of the harbour although it can be quite exposed to swell. The harbour is busy and there is always something going on. As well as freighters and a few cruise ships, the P&O liner Canberra visited while I was there and also ships of the Portuguese, French and British navies. I was near the outer edge of the anchorage and one morning I came out on deck to find the stern of a huge freighter towering over me—she was being turned around by tugs. My first thought was that the pilot was probably pretty irritated by Oborea and the other yachts being in his way, but he leant over the bridge wing (now almost overhead) and gave me a cheerful wave as if to say "Don't worry! I'm not going to hit you." Funchal was my final Portuguese port and I got the last (and thirtieth) rubber stamp in my cruising permit and set off for the Spanish Canary Islands two hundred and fifty miles to the south. There are seven Canary Islands, but I planned to visit only the two most westerly and my destination was Santa Cruz de La Palma. Winds were light for the crossing, but after noon on the second day I saw the mountains of La Palma looming out of the haze far above the clouds. I also saw my biggest school of dolphins, over fifty of them playing around the boat. Once in the lee of the island (which claims to be the highest for its size in the world) progress slowed down to a crawl and it was after midnight when I entered the artificial harbour of Santa Cruz. There is a little basin set aside for small craft, but in the dark it seemed to be completely full so I anchored just outside. Next morning I found it was indeed full, but by rowing a stern anchor back into the mess of boats I could haul myself aft until I was at least semi-legal. (On leaving I had to dive to disentangle this anchor.) This was one of my least pleasant harbours, boats have to be anchored fore and aft so that they do not swing, and still they bump at every wind shift. Access to fresh water, and even to the town seemed unnecessarily awkward. Compared to Portugal though entry formalities were very casual—they took little interest in visiting yachts and there were no charges. Also after Portugal Santa Cruz seemed much more modern with many high-rise apartment buildings. Mainly white, these blended in surprisingly well with the traditional whitewashed flat roofed Spanish architecture. Streets were dirty though, and lacked the beautiful mosaic sidewalks. Grocery stores had a far wider selection, but were more expensive. My last stop in European waters was at Hierro, the smallest and most south westerly of the Canaries and little visited by yachts. The capital, Valverde, is three miles inland and is served by the little artificial harbour of Puerto de la Estaca tucked at the foot of steep cliffs. There are half a dozen houses and one general store at the port. It was interesting that after having Oborea's particulars entered by hand in dusty ledgers in half a dozen European ports, in this the smallest, they went into a computer! In a few days I was ready for the Atlantic crossing, but the weather did not cooperate. The North East Trades often extend as far north as the Canaries, but we were getting steady south west winds. In the harbour, designed for protection from the prevailing winds, the swells were quite uncomfortable, and the wind funnelled down from the cliffs in gale-force gusts interspersed with flat calms. After three days of this I had had enough—I would rather be uncomfortable at sea than uncomfortable surrounded by rocks—so on November 7th I cleared for Bridgetown, Barbados.