I remained four days at Fayal, and that was two days more than I had

intended to stay. It was the kindness of the islanders and their

touching simplicity which detained me. A damsel, as innocent as an

angel, came alongside one day, and said she would embark on the

Spray if I would land her at Lisbon. She could cook flying-fish, she

thought, but her forte was dressing bacalhao. Her brother Antonio

who served as interpreter, hinted that, anyhow, he would like to make

the trip. Antonio's heart went out to one John Wilson, and he was

ready to sail for America by way of the two capes to meet his friend.

"Do you know John Wilson of Boston?" he cried. "I knew a John

Wilson," I said, "but not of Boston." "He had one daughter and one

son," said Antonio, by way of identifying his friend. If this reaches

the right John Wilson, I am told to say that "Antonio of Pico

remembers him."

I set sail from Horta early on July 24. The southwest wind at the time

was light, but squalls came up with the sun, and I was glad enough to

get reefs in my sails before I had gone a mile. I had hardly set the

mainsail, double-reefed, when a squall of wind down the mountains

struck the sloop with such violence that I thought her mast would go.

However, a quick helm brought her to the wind. As it was, one of the

weather lanyards was carried away and the other was stranded. My

tin basin, caught up by the wind, went flying across a French

schoolship to leeward. It was more or less squally all day, sailing

along under high land; but rounding close under a bluff, I found an

opportunity to mend the lanyards broken in the squall. No sooner had

I lowered my sails when a four-oared boat shot out from some gully

in the rocks, with a customs officer on board, who thought he had

come upon a smuggler. I had some difficulty in making him

comprehend the true case. However, one of his crew, a sailorly chap,

who understood how matters were, while we palavered jumped on

board and rove off the new lanyards I had already prepared, and with

a friendly hand helped me "set up the rigging." This incident gave the

turn in my favour. My story was then clear to all. I have found this

the way of the world. Let one be without a friend, and see what will

happen!

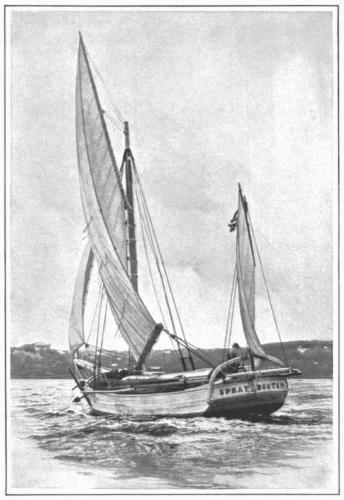

Passing the island of Pico, after the rigging was mended, the Spray

stretched across to leeward of the island of St. Michael's, which she

was up with early on the morning of July 26 the wind blowing hard.

Later in the day she passed the Prince of Monaco's fine steam-yacht

bound to Fayal, where, on a previous voyage, the prince had slipped

his cables to "escape a reception" which the padres of the island

wished to give him. Why he so dreaded the "ovation" I could not

make out. At Horta they did not know.

Since reaching the islands I had lived most luxuriously on fresh

bread, butter, vegetables, and fruits of all kinds. Plums seemed the

most plentiful on the Spray, and these I ate without stint. I had also a

Pico white cheese that General Manning, the American consul-

general, had given me, which I supposed was to be eaten, and of this

I partook with the plums. Alas! by night-time I was doubled up with

cramps. The wind, which was already a smart breeze, was increasing

somewhat, with a heavy sky to the sou'west. Reefs had been turned

out, and I must turn them in again somehow, Between cramps I got

the mainsail down, hauled out the earings as best I could, and tied

away point by point, in the double reef. There being sea-room, I

should, in strict prudence, have made all snug and gone down at once

to my cabin. I am a careful man at sea, but this night, in the coming

storm, I swayed up my sails, which, reefed though they were, were

still too much in such heavy weather; and I saw to it that the sheets

were securely belayed. In a word, I should have laid to, but did not. I

gave her the double-reefed mainsail and whole jib instead, and set

her on her course. Then I went below, and threw myself upon the

cabin floor in great pain. How long I lay there I could not tell, for I

became delirious. When I came to, as I thought, from my swoon, I

realized that the sloop was plunging into a heavy sea, and looking out

of the companionway, to my amazement I saw a tall man at the helm.

His rigid hand, grasping the spokes of the wheel, held them as in a

vice. One may imagine my astonishment. His rig was that of a

foreign sailor, and the large red cap he wore was cockbilled over his

left ear, and all was set off with shaggy black whiskers. He would

have been taken for a pirate in any part of the world. While I gazed

upon his threatening aspect I forgot the storm, and wondered if he

had come to cut my throat. This he seemed to divine. "Señor," said

he, doffing his cap, "I have come to do you no harm." And a smile,

the faintest in the world, but still a smile, played on his face, which

seemed not unkind when he spoke. "I have come to do you no harm.

I have sailed free," he said, "but was never worse than a

contrabandista. I am one of Columbus's crew," he continued. "I am

the pilot of the Pinta come to aid you. Lie quiet, señor captain," he

added, "and I will guide your ship to-night. You have a calentura, but

you will be all right to-morrow." I thought what a very devil he was to

carry sail. Again, as if he read my mind, he exclaimed "Yonder is the

Pinta ahead; we must overtake her. Give her sail; give her sail! Vale,

vale, muy vale!" Biting off a large quid of black twist, he said: "You did

wrong, captain, to mix cheese with plums. White cheese is never safe

unless you know whence it comes. Quien sabe, it may have been from

leche de Capra and becoming capricious -"

"Avast, there." I cried. "I have no mind for moralizing." I made shift to

spread a mattress and lie on that instead of the hard floor, my eyes all

the while fastened on my strange guest, who, remarking again that I

would have "only pains and calentura," chuckled as he chanted a wild

song:

High are the waves, fierce, gleaming,

High is the tempest roar!

High the sea-bird screaming!

High the Azore!

I suppose I was now on the mend, for I was peevish, and complained:

"I detest your jingle. Your Azore should be at roost, and would have

been were it a respectable bird!" I begged he would tie a rope-yarn on

the rest of the song, if there was any more of it. I was still in agony.

Great seas were boarding the Spray, but in my fevered brain I thought

they were boats falling on deck, that careless draymen were throwing

from wagons on the pier to which I imagined the Spray was now

moored, and without fenders to breast her off. "You'll smash your

boatsl" I called out again and again, as the seas crashed on the cabin

over my head. "You'll smash your boats, but you can't hurt the Spray.

She is strong!" I cried.

I found, when my pains and calentura had gone, that the deck, now as

white as a shark's tooth from seas washing over it, had been swept of

everything movable. To my astonishment, I saw now at broad day that

the Spray was still heading as I had left her, and was going like a race-

horse. Columbus himself could not have held her more exactly on her

course. The sloop had made ninety miles in the night through a rough

sea. I felt grateful to the old pilot, but I marvelled some that he had not

taken in the jib. The gale was moderating, and by noon the sun was

shining. A meridian altitude and the distance on the patent log, which I

always kept towing, told me that she had made a true course throughout

the twenty-four hours. I was getting much better now, but was very

weak, and did not turn out reefs that day or the night following,

although the wind fell light; but I just put my wet clothes out in the sun

when it was shining, and, lying down there myself, fell asleep. Then

who should visit me again but my old friend of the night before, this

time, of course, in a dream. "You did well last night to take my advice,"

said he, "and if you would, I should like to be with you often on the

voyage, for the love of adventure alone." Finishing what he had to say,

he again doffed his cap and disappeared as mysteriously as he came,

returning, I suppose, to the phantom Pinta. I awoke much refreshed,

and with the feeling that I had been in the presence of a friend and a

seaman of vast

experience. I

gathered up my

clothes, which

by this time

were dry, then,

by inspiration, I

threw overboard

all the plums in

the vessel.

[top] [return to the Azores page] [home]