JULY 10, eight days at sea, the Spray was twelve hundred miles east

of Cape Sable. One hundred and fifty miles a day for so small a

vessel must be considered good sailing. It was the greatest run the

Spray ever made before or since in so few days. On the evening of

July 14 in better humour than ever before, all hands cried, "Sail ho!"

The sail was a barkantine, three points on the weather bow, hull

down. Then came the night. My ship was sailing along now without

attention to the helm. The wind was south; she was heading east. Her

sails were trimmed like the sail of the nautilus. They drew steadily

all night. I went frequently on deck, but found all well. A merry

breeze kept on from the south. Early in the morning of the 15th the

Spray was close aboard the stranger, which proved to be La Vaguisa

of Vigo, twenty-three days from Philadelphia, bound for Vigo. A

lookout from his masthead had spied the Spray the evening before.

The captain, when I came near enough, threw a line to me and sent a

bottle of wine across slung by the neck, and very good wine it was.

He also sent his card, which bore the name of Juan Gantes. I think he

was a good man, as Spaniards go. But when I asked him to report me

"all well" (the Spray passing him in a lively manner), he hauled his

shoulders much above his head; and when his mate, who knew of my

expedition, told him that I was alone, he crossed himself and made

for his cabin. I did not see him again. By sundown he was as far

astern as he had been ahead the evening before.

There was now less and less monotony. On July 16 the wind was

northwest and clear, the sea smooth, and a large bark, hull down,

came in sight on the lee bow, and at 2.30 p.m. I spoke to the stranger.

She was the bark Java of Glasgow, from Peru for Queenstown for

orders. Her old captain was bearish, but I met a bear once in Alaska

that looked pleasanter. At least, the bear seemed pleased to meet me,

but this grizzly old man! Well, I suppose my hail disturbed his siesta,

and my little sloop passing his great ship had somewhat the effect on

him that a red rag has upon a bull. I had the advantage over heavy

ships, by long odds in the light winds of this and the two previous

days. The wind was light; his ship was heavy and foul, making poor

headway, while the Spray, with a great mainsail bellying even to light

winds, was just skipping along as nimbly as one could wish. "How

long has it been calm about here?" roared the captain of the Java as I

came within hail of him. "Dunno, cap'n," I shouted back as loud as I

could bawl. "I haven't been here long." At this the mate on the

forecastle wore a broad grin. "I left Cape Sable fourteen days ago," I

added. (I was now well across toward the Azores.) "Mate," he roared

to his chief officer - "mate, come here and listen to the Yankee's yarn.

Haul down the flag, mate, haul down the flag!" In the best of humour,

after all, the Java surrendered to the Spray.

The acute pain of solitude experienced at first never returned. I had

penetrated a mystery, and, by the way, I had sailed through a fog. I

had met Neptune in his wrath, but he found that I had not treated him

with contempt, and so he suffered me to go on and explore.

In the log for July 18 there is this entry: "Fine weather, wind south-

southwest. Porpoises gamboling all about. The S.S. Olympia passed

at 11.30 a.m., long. W. 34º 50'."

"It lacks now three minutes of the half-hour," shouted the captain, as

he gave me the longitude and the time. I admired the businesslike air

of the Olympia; but I have the feeling still that the captain was just a

little too precise in his reckoning. That may be all well enough,

however, where there is plenty of searoom. But over-confidence, I

believe, was the cause of the disaster to the liner Atlantic, and many

more like her. The captain knew too well where he was. There were

no porpoises at all skipping along with the Olympia! Porpoises

always prefer sailing-ships. The captain was a young man, I

observed, and had before him, I hope, a good record.

Land ho! On the morning of July 19 a mystic dome like a mountain

of silver stood alone in the sea ahead. Although the land was

completely hidden by the white, glistening haze that shone in the sun

like polished silver, I felt quite sure that it was Flores Island. At half-

past four p.m. it was abeam. The haze in the meantime had

disappeared. Flores is one hundred and seventy-four miles from

Fayal, and although it is a high island, it remained many years

undiscovered after the principal group of the islands had been

colonized.

Early on the morning of July 20 I saw Pico looming above the clouds

on the starboard bow. Lower lands burst forth as the sun burned away

the morning fog, and island after island came into view. As I

approached nearer, cultivated fields appeared, "and oh, how green the

corn!" Only those who have seen the Azores from the deck of a vessel

realize the beauty of the mid-ocean picture.

At 4.30 p.m. I cast anchor at Fayal, exactly eighteen days from Cape

Sable The American consul, in a smart boat, came alongside before the

Spray reached the breakwater, and a young naval officer, who feared

for the safety of my vessel, boarded, and offered his services as pilot.

The youngster, I have no good reason to doubt, could have handled a

man-of-war, but the Spray was too small for the amount of uniform he

wore. However, after fouling all the craft in port and sinking a lighter,

she was moored without much damage to herself. This wonderful pilot

expected a "gratification" I understand, but whether for the reason that

his government, and not I, would have to pay the cost of raising the

lighter, or because he did not sink the Spray, I could never make out.

But I forgive him.

It was the season for fruit when I arrived at the Azores, and there was

soon more of all kinds of it put on board than I knew what to do with.

Islanders are always the kindest people in the world, and I met none

anywhere kinder than the good hearts of this place The people of the

Azores are not a very rich community. The burden of taxes is heavy,

with scant privileges in return, the air they breathe being about the only

thing that is not taxed. The mother-country does not even allow them a

port of entry for a foreign mail service. A packet passing never so close

with mails for Horta must deliver them first in Lisbon, ostensibly to be

fumigated, but really for the tariff from the packet. My own letters

posted at Horta reached the United States six days behind my letter

from Gibraltar, mailed thirteen days later.

The day after my arrival at Horta was the feast of a great saint. Boats

loaded with people came from other islands to celebrate at Horta, the

capital, or Jerusalem of the Azores. The deck of the Spray was crowded

from morning till night with men, women, and children. On the day

after the feast a kind-hearted native harnessed a team and drove me a

day over the beautiful roads all about Fayal, "because," said he, in

broken English, "when I was in America and couldn't speak a word of

English, I found it hard till I met someone who seemed to have time to

listen to my story, and I promised my good saint then that if ever a

stranger came to my country, I would try to make him happy."

Unfortunately, this gentleman brought along an interpreter, that I might

"learn more of the country." The fellow was nearly the death of me,

talking of ships and voyages, and of the boats he had steered, the last

thing in the world I wished to hear. He had sailed out of New Bedford,

so he said, for "that Joe Wing they call 'John.' " My friend and host

found hardly a chance to edge in a word. Before we parted my host

dined me with a cheer that would have gladdened the heart of a prince,

but he was quite alone in his house. "My wife and children all rest

there," said he, pointing to the churchyard across the way. "I moved to

this house from far off," he added, "to be near the spot, where I pray

every morning."

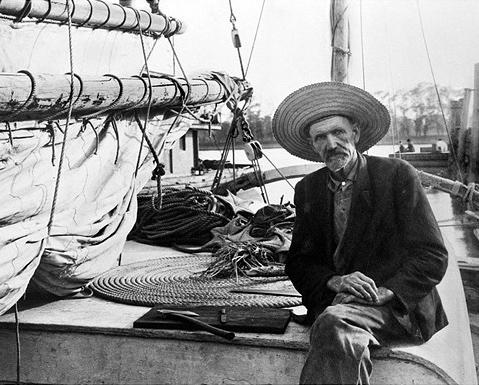

from

SAILING ALONE AROUND THE WORLD

By Joshua Slocum

1900

[continue]