Chapter 5 — The Voyage Continues

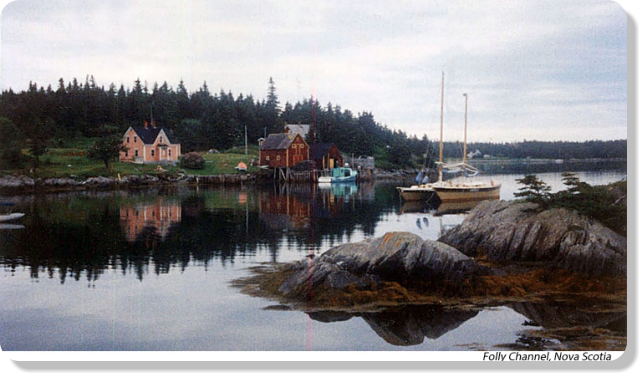

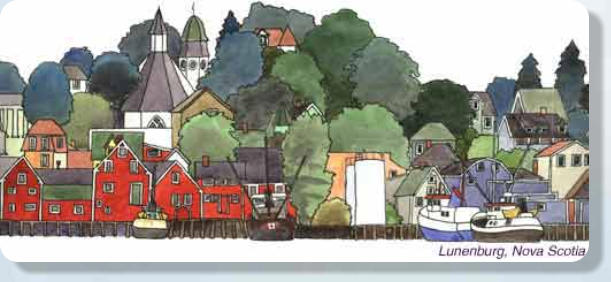

Still single handed I got away from Bermuda under sail about noon, tacking out through Town Cut against a light east wind and then taking a couple more long tacks to put me well clear of the off-lying reefs before I set course due north. Destination: Lunenburg, Nova Scotia. Conditions remained perfect for the next couple of days and I passed two yachts; a big old British brigantine that had left Bermuda four hours ahead of me and a small schooner. On the third day a small naval vessel was performing complicated manoeuvres on the eastern horizon, finally she steamed over close to me (she was the USS Blakely) and asked my nationality. She must have been satisfied as she steamed off to the north west. That night I left the warm seas of the Gulf Stream. The water temperature dropped six degrees Celsius in a few miles and was to drop another ten degrees before I reached my destination. The following day was cloudy and I could not get a sun sight to find out how far off my dead reckoning the Gulf Stream had set me, but later in the morning a large bulk freighter bound for Europe passed six miles astern and I called him for a position. His satellite reading, accurate to a tenth of a mile put me thirty miles east and twenty miles north of my reckoning. The Gulf Stream had contributed to a record day's run of one hundred and ninety miles. That evening the wind, which was now southerly, began to increase and by midnight it was blowing a gale and I was surfing down ten to twelve foot seas with only my eighty seven square foot jib set. It was a dark night and the phosphorescence was brilliant. Breaking waves seemed outlined in neon lights while between the hulls swirled a river of fire. Two rocket trails stretched out astern. The biggest shock to my system was the temperature. For the past three months I had been wearing a bathing suit by day and a T shirt or sweat shirt and shorts by night. Now I had on a T shirt, a sweat shirt, heavy wool sweater, down vest and raingear and I was still cold! After dawn the wind which had got up to thirty five or forty knots started to subside, and by noon I had full working sail up again. A hazy noon sight put me at latitude 41º 55' north, and during the afternoon a foggy rain started to fall. I was definitely getting near the Maritimes! During the night the fog thickened and I was travelling in a circle of visibility of less than a hundred yards diameter. The masthead light threw brilliant red, green and white beams out into the night. The fog continued all next day, dense at sea level but thin above allowing a hazy sun to shine through. Shearwaters flew around the boat, their wingtips skimming the waves as we continued on course at five to six knots. By mid morning I could pick up coastal radio beacons and get a fix. I headed for the beacon on Cross Island at the mouth of Lunenburg Bay. In the early afternoon I heard the foghorn of a large vessel which passed close enough for me to hear her engines but I never saw her. At half past two the fog lifted briefly and I saw a fishing boat on a parallel course to mine about a mile off; I hoped she was heading for Lunenburg too! At four there was another break in the fog and it was LAND HO!! Cross Island ahead and Rose Point on the port bow. A quick bearing before the fog closed in again put me about four miles off, and the next thing I saw was the Cross Island whistle buoy (the locals very aptly call these buoys 'groaners'). As I sailed through the gap between Cross Island and Rose Point I sailed out of the fog bank and had a sparkling sail up Lunenburg Bay in brilliant sunshine to finally drop anchor in the sheltered harbour at a quarter to six. Seven hundred and fifty miles from Bermuda in five days and six hours. My crew for the next leg of the journey would not be joining me for another month, but I had introductions to a number of people in the area and I looked forward to spending time on these waters that I had not visited for twenty eight years. Lunenburg has changed little. It is still a major fishing centre and the quaint old houses still climb steeply away from the waterfront; there is not a high-rise in sight. The Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic is here and their Grand Banks schooner, the Teresa E. Connor is hauled out for a refit in the same yard that built her fifty years before (the same yard that built both Bluenoses). Almost the entire bow is being replaced: stem post, frames and planking, and again the sound of the caulker's mallet rings across the harbour. There are few yachts around this early in the season (the end of June) never more than two besides Oborea anchored in the harbour. The last cold wet days of the voyage had shown up the weaknesses in my elderly rain gear, so I went out and bought a set of fishermen's oilies (made in Ontario) and a pair of heavy black rubber boots. Wearing these boots I felt less conspicuous as I walked about town. Sailing in these foggy waters I sorely missed my echo sounder which had been out of action for the past year. I had been carrying a new transducer since I left Toronto but had no opportunity to install it. With the five foot tides here I determined to do it on the shingle beach on the south side of the harbour. A seventy five year old fisherman already had his boat on the beach, painting the bottom. He told me many tales about his youth, long lining from schooners on the Banks, and by the end of the day my transducer was installed, his boat was painted and I could understand over half of what he was saying. After five days in Lunenburg the sun burst through the fog again and I sailed eighteen miles south and west to the LaHave Islands off the mouth of the LaHave River. These rocky spruce covered islands are a little like the Thousand Islands with the addition of surf breaking on the Atlantic side and five foot tides. In the old days when there were few roads on the mainland and all communication was by sea, almost all the islands had houses on them. Most are now abandoned although a few are still used as summer cottages and one or two of the old families have hung on. I anchored in Folly Channel between Outer Hirtle Island and Covey Island. The Covey Island Boatworks which builds yachts and fishing boats has joined the migration to the mainland and the old buildings are now deserted. On the other side of the channel lives a crusty old fisherman, Mansfield Hirtle, the last of his family to live on the island. Within half an hour of my arrival Mansfield was aboard sharing a glass of rum and complaining about the state of the fisheries. He was the first of several visitors which included Tom who keeps the light on Mosher Island and who has, with his wife Anne, carved a small farm out of the bush on the island where they grow vegetables for the market and raise prize winning goats. A couple of mornings later I rowed to Bush Island (joined to the mainland by a causeway) where John of the Covey Island Boatworks now lives. The distance would be equivalent to crossing the Outer Harbour from the TMCC, but I had to row a compass course in the dinghy because of the fog. Next day I moved Oborea to the cove off John and Peggy's house. The climate here is unusual. Ten miles inland at Bridgewater it may be sunny and twenty six degrees, while on the coast if there is a sea breeze it can be foggy and only get up to fifteen degrees; you can choose your own climate. One weekend a group of us sailed on Oborea for an overnight visit to windswept Cape LaHave Island. We built a fire on the beach, roasted a leg of goat and drank home made beer until late in the night. We kept warm by the fire but beyond its dancing light the temperature dropped to nine degrees. This was on a July day when the temperature reached forty degrees in Toronto. Finally my crew arrived and it was time to leave this friendly coast and set off onto the Atlantic.