It all started with a phone call:

"Are you the owner of the Wharram Catamaran that is for sale?"

"Yes"

"Well it is not actually the boat we are interested in; it is you. We are looking for an experienced multihull sailor

to crew on a trimaran delivery to Newport, Rhode Island."

"When are you leaving?"

"The day after tomorrow. Why don't you come down and have a look at the boat now; she is Pacific Challenge at

the end of B dock"

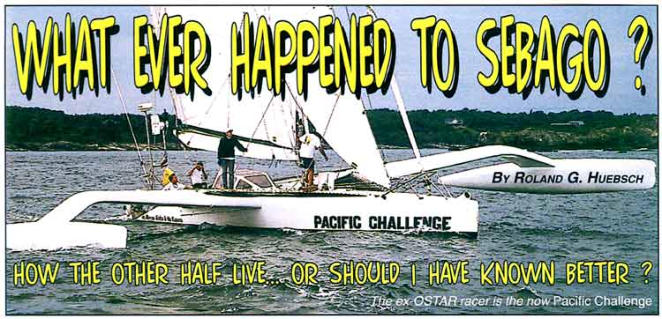

In less than forty minutes I was there. I had already seen her; she looked more like an aircraft or even a spaceship

than a boat, a great spidery racing machine. Aboard, I learned a lot more details. Ex OSTAR racer Sebago, she

was designed by Adrian Thompson and built entirely of carbon fibre and epoxy (I am not really up on all these

technical developments: to me carbon brings to mind used matches or pencil leads but I was assured she was

stronger than steel). The main hull is sixty feet long but less than five feet wide and of monocoque construction

with no stringers. The single crossarm on each side starts well aft of amidships and sweeps forward and up and

then down in a graceful arc to the fairly small amas; overall beam is also sixty feet. Shorter arms run out from the

aft side of the cockpit to the midpoint of the main arms to support the long mainsheet track. The carbon fibre

mast carries a fully battened brute of a mainsail of 1,200 square feet including an enormous roach. Forward of

the mast is a 7/8ths roller furling jib and a fully battened staysail with a continuous curve from the head through

the clew to the foot, like a windsurfer sail. The present owners

had bought the boat in Ireland, completely restored and re-

rigged her and now she was on her way to her new home port of

Honolulu. The third crew member had been unable to get his

leave from the Irish navy extended and that was why I had been

approached. Built as a single-hander accommodations are

minimal, and with three aboard she was pretty cramped. But

who could give up an opportunity like this to travel at the

racers edge? Certainly not me and at 1400 hours on Saturday

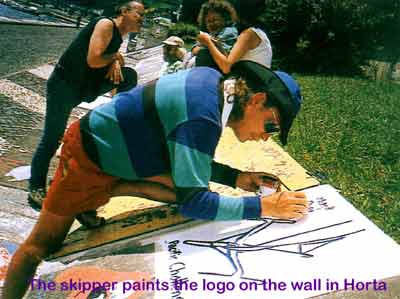

the first of July we set sail from Horta and were soon reaching

along the south side of Faial at seven to ten knots – those gull

like cross arms flexing gently like the wings of an airliner.

Pacific Challenge – rather cheeky perhaps to challenge the

mightiest ocean on earth, but at least this was the Atlantic we

were crossing now so I felt relatively safe and, besides, along

the sides aft was written He Mana'o Aloha O Nã Kupuna - In

the Spirit of our Forefathers - this should help appease the

gods.

Clear of the island the already low ceiling dropped lower still

and a series of rain squalls blew through; we put in two reefs with hardly any change in speed. A dark, wet night

but we are travelling fast. Before dawn we can see the lights of Flores off to the north. During the morning the sun

comes out and the wind goes light leaving us rolling around in sloppy seas and by noon we have covered 175 miles

from Horta. During the afternoon the wind picks up from the north and soon we are travelling fast again; before

nightfall we put back the second reef. It is also at around this time that we discover that half the cooking gas

cylinders have been left behind in Ireland – we may not have enough to last the voyage so limit ourselves to a hot

dinner every other day; all part of the adventure I suppose. Another fast wet night. The carbon fibre construction

is like spring-steel and the boat bounces and shimmies through the waves twitching her tail. Below it is very noisy

and lying in the bunk I try to decide how to describe the feeling; finally I come up with it – a run-away subway

train. At every watch change dripping wet-weather gear brings more water below and soon everything is pretty

damp.

Let me take you on a tour through our luxury accommodation. The cockpit is about eight or nine feet long and

three feet wide and the forward three or four feet are covered by a doghouse. This is low, just high enough to sit

on the floor under it, while the helmsman sits aft and looks over it. The forward three feet of the cockpit floor

slope up and in this part is a circular hatch leading below, rather like dropping down the conning tower of a

submarine. This hatchway is the only place where it is possible to stand upright below and it leads into a space

about four feet wide and three feet fore and aft – the hallway. The floor is the bottom of the boat and is curved.

Aft, under the cockpit, is the master bedroom – a single bunk the width of the hull with a little storage under it,

and I almost forgot, the hallway is also the galley with a little bench seat to port and a single burner swinging

stove to starboard. No counter area. Heading forward from the galley is a crawlspace about four feet long under

the main cross-beam. The sides are lined with canvas pouches for stores. Continuing forward we enter the Grand

Salon – a space some eight feet long and oval in cross-section about five feet high and four wide – like being in a

big plastic pipe. The navigation table crosses the forward end of the salon with a short bench seat to starboard.

Shelves below carry fresh water bottles and below that the batteries. The walls are lined with more canvas

pouches and the space is lit by a nine inch square skylight. On the floor is a foam pad – the second bunk. (The

third crew member is on watch). And this is all the accommodation – it ends at the mast bulkhead. Forward of

the mast the space below is accessible by a hatch forward of the daggerboard which cannot be opened in rough

weather. In any case these boats get their speed from their very light weight so only minimal stores and

equipment can be carried. Aft of the cockpit another hatch leads to the steering gear where between the steering

cables and quadrants and beside the hydraulic ram of the autopilot there is just room to squeeze in a bucket

toilet.

By daybreak the bulk of the cloud is behind us, but we are still sailing fast under sunny skies. At noon we are in

position 39° 17.8' north, 38° 38.9' west for a day's run of 298 miles (compare this with Oborea's best ever run of

192 miles!) By dusk though the wind has gone very light and we turn on the Honda outboard motor for a while.

During Tuesday morning we pick up a light south-west wind and by noon our day's run is 240 miles. We take

advantage of the smooth and sunny afternoon to spread our clothes and sleeping bags out on the trampolines to

dry a bit; we also haul The Skipper part way up the mast to repair the lazyjacks that had broken during the rough

going earlier. Yesterday we ran a temporary cable from the engine battery aft to the main batteries amidships so

that when the motor is running it can help the wind generator keep the main batteries charged. Today that cable

shorted out creating billows of smoke as the insulation melted. It has also fried the autopilot so that from now on

we shall have to hand steer all the way. We are fortunate though that it was nothing worse. In the evening the

wind veers to the south-west and increases as another front approaches.

Bucking along leaving trails of phosphorescence all night, but by morning the wind dies away to be replaced by

fog and rain – we are just south of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. There are schools of dolphins leaping

round us though to keep us entertained and by noon we have covered 260 miles. In the evening the wind returns

from the south-east and we surf all night under alternating moonlight and

rain showers.

By Thursday morning the waves have lengthened out and we are surfing

fast. The Skipper is an old Hawaiian hand and I learn a lot from him about

how to keep the boat going at top speed under these conditions –

feathering across the face of a swell like a board surfer; the spray is flying

and I am soaking wet but having a ball. Our day's run is 245 miles but

there is no sun and the long swells are lead-grey. Our average speed so far

has been 240 miles a day and the crew are making bets whether we shall

be in Newport Sunday night or Monday morning. Foolish mortals. The

wind dies out by sunset and again we motor for a while

A hot, hot sun and little wind all day – our days run drops to 132 miles.

During the afternoon a light breeze from the south gets us back up to ten

knots, but we pick up bad news on the radio: a tropical storm, Barry, has

formed between Bermuda and South Carolina and is heading north-east

on a collision course with us. We decide to play it safe and tack to the

south-east until Barry is safely past rather than try and race him. The wind

goes light again after dark and we sail slowly through a beautiful warm

moonlit night.

All Saturday we continue heading south-east through light fluky winds

under sunny skies, hard to tell there is a tropical storm anywhere around.

What with this back-tracking and the gulf-stream pushing us north-east

our noon position is only 12 miles south of where we were yesterday. A

week out of Horta and we have covered 1,360 miles with only about 700 to

go. The Skipper calls his office to tell them of our detour around Barry and not to expect us before Wednesday

now. In the evening we listen to the weather reports out of the USA and learn that the storm is speeding up; we

can safely tack again and cross between two and three hundred miles behind it. Going west though, the winds

start to increase and soon we are heading into a brilliant sunset ringed by great cumulus clouds and thunder

heads. We put the third reef in the mainsail for the first time on this trip. All night we are surrounded by lightning

storms with periods of heavy rain, but in the morning the clouds clear although the wind and waves are still

increasing. It is the wildest day of the trip surfing through brilliant blue seas with whitecaps all around us. The

exhilaration is fantastic as the bows dip and a powerful swell lifts the stern and the boat accelerates forward with

the bows half buried and long plumes of spray curve away on each side and the speed builds to fifteen or eighteen

knots. The windward ama skims the wavetops like an airborne seaplane while that to leeward is almost buried

The daggerboard hums and the whole craft trembles with excitement. And through it all the helm is feather-light

without a hint of broaching or lack of control. We are high on speed and laughing in glee! Below, the noise and

motion are something else – I thought about how to make a Pacific Challenge simulator… Lash a length of five

foot diameter plastic tube to the back of a pickup truck and climb in. Have someone drive the truck at high speed

along the worst and most winding lanes they can find, taking care not to avoid potholes and at the same time

have burley men pound the tube with wooden mallets. Anytime you stick your head out have them hurl a bucket

of seawater at you. Now try and plot an accurate position on a chart!

Because of our tack last night we have made good only 108 miles toward Newport by noon, but the wild

conditions continue until late in the evening when things start to calm down a bit, and by morning we shake out

two reefs (we cannot shake out the last one as the top of the sail track has pulled away from the mast). By noon

we are becalmed and rolling about uncomfortably in sloppy seas, but we have run 218 miles since noon yesterday.

During the afternoon the wind picks up a bit and we are able to make some speed –

especially when the confused seas start to flatten out.

Tuesday the 11th of July dawns flat calm under a baking sun; a good day for drying

clothes on the trampolines, but not for making progress toward Newport. We are

running the engine at only a little above idle speed to conserve fuel which is getting

very low. This gives us a speed through the water of four and a half or five knots but

at least we are moving. Originally we had decided to keep two tanks of fuel for our

arrival in Narragansett bay, but now with only two left we have agreed that one will

be quite enough!

In the evening we shut down the engine again and ghost along at a knot or two but

dawn comes with no hint of wind on the hazy horizon and the sea an oily calm. We

decide that half a tank of fuel will be enough to enter Newport and we fire up the

motor and start to inch along again. Less than 120 miles to go but at this rate we are

going to be out here for another two or three days – we are all feeling glum at the

prospect. During the morning we spot a large tanker overtaking us a few miles to

starboard – nothing new in this, we had seen big ships almost every day, but when

she slowly starts to change course and swing toward us we sit up and take notice.

We turn on the VHF radio:

"Neptune Atomi to the sailing vessel on my bow, over"

"This is the sailing vessel ahead of you Neptune Atomi"

"Are you by any chance the trimaran Pacific Challenge?"

"Affirmative"

"Are you aware that the US Coastguard in New York has put out an overdue vessel

report on you?"

We were dumfounded; the only ETA we had given to any one was Wednesday and this was still ten o'clock

Wednesday morning. We explained to the captain of the Neptune Atomi, but he remained concerned wanting to

know if he could offer any kind of assistance. He told us there was a Coastguard vessel in the area and he would

report our position. We overheard the conversation, but the Coastguard was out of range of our radio so the

tanker continued to relay. The Coastguard, too, were concerned asking if we needed anything and half in joke we

said we needed some gasoline. No problem replied the Coastguard, we can be with you in about three hours. We

were quick to explain that we were in absolutely no kind of danger and this was to be strictly if it was no

inconvenience to them. No bother came the reply – we're just cruising.

Within fifteen minutes we could talk to the coast guard directly and the tanker captain asked if he might continue

his voyage. The spirit of the sea is not dead! Diverting that tanker had probably cost the owners several thousand

dollars but the captain had not left until he was sure that there was nothing more he could do.

We were going to get fuel! We could be in port in lass than twelve hours! We would not run out of cooking gas!

We toasted the coast guard in the first hot coffee we had had since the beginning of the trip. The Skipper made a

call to his partner and discovered what had happened. He (the partner) had called the Coastguard merely to ask if

anyone had seen us, not because he was concerned but because he was curious about our position. The

Coastguard had interpreted this as a missing vessel report! An hour later the fog rolled in pea-soup thick and the

Coast-guard called:

"How is your visibility?"

"Less than an eighth of a mile"

"Same here, I guess we are in the same bank but we have you on radar"

Pacific Challenge has radar too, but with a range of only about five miles the screen was blank. Within an hour

though we had an echo and we could hear the foghorn of the Coastguard cutter as he stopped a quarter mile

astern and put out his inflatable dinghy and soon it appeared through the fog with eight people aboard. I suppose

the Coastguard are understandably cautious boarding strange vessels and the dinghy put four armed men aboard

us and stood off, but once assured that we were peaceful sailors they came in again to load five of our jerrycans

and head back to the mother ship which was now visible towering over us like a white castle less than 100 yards

off our quarter. The four men who remained aboard could not have been nicer, although once aboard they had to

make a vessel inspection and of course they found a couple of things wrong. Our lifejackets were not USCG

approved (remember the boat had just been refitted in Ireland) The lieutenant apologised for having to report

this and added a note to his form explaining that we had good lifejackets. In the same way he explained how the

red and green navigation lights on our bow (which had ceased working after spending so much time immersed)

were defective due to "the length and nature of the voyage"

We had our gasoline tanks filled within an hour and when we asked what it would cost us we were told "nothing –

it is what we do" We bid the Coastguard a grateful goodbye and headed off into the fog at our power cruising

speed of ten knots.

Since leaving Horta we had been aiming for the LANBY (Large Automatic Navigation Buoy) which has replaced

the Nantucket Shoals Lightship about 100 miles from Newport, but we actually passed well south of it and did not

even see it on radar. In fact our first positive fix was when we saw the much smaller buoy "8DS" about thirty

miles further on. Our whole approach to the coast was a bit nerve wracking with the darkness, the thick fog, lots

of fishing boats around and the extensive Nantucket Shoals to starboard. Number One (a good New-Englander)

was steering, and The Skipper kept his eyes glued to the radar while I was below frequently updating our position

on the chart and sending up course changes. We were now aiming for the Brenton Reef light tower at the

entrance to Narragansett Bay, but when we came to where it should be we could not find it. All three GPS's

(satellite navigation devices) aboard said we were there but there was no sign of it – we could not even hear the

foghorn. We sailed in a complete circle looking for it, to the confusion of the Narragansett Bay Pilot Boat that

loomed briefly out of the fog. By now though I could identify the points at each side of the mile wide entrance on

the radar and relate them to the chart and so we continued at dead slow speed with Number One out on the bow

looking for any sight of anything, The Skipper at the helm, and me doing my best to guide him in by radar. Like

this we sailed four and a half miles up the bay and around the south end of Goat Island into Newport Harbor and

the first thing we actually saw was the buoy off the south tip of the island, followed shortly by the vague outlines

of the condos ashore. We circled the moorings (in itself not an easy task with a sixty foot wide boat) found a

vacant one and picked it up at five thirty in the morning (local time) twelve days and fifteen hours from Horta.

We broke out our few remaining beers to celebrate as we waited for the dawn and for the fog to lift and as it got

lighter we discovered we were in good company; what I had taken in the dark for a floating dock turned out to be

the eighty-five foot French catamaran Commodore Explorer that had recently won the Jules Verne prize by

sailing around the world in less than eighty days.

We hitched a ride ashore with a passing teenager (Pacific Challenge carries no dinghy) and headed for the first

restaurant to open where we had a Big Breakfast and after that we each ordered another Big Breakfast. We

discovered that the only customs man in Newport was checking in a cruise ship and would be several hours so we

set up camp at an outdoor café hoisting the Q flag and the Hawaiian flag on the table's umbrella pole and waited.

By noon we were officially in the USA. That afternoon we split up – Number One to return to his home in

Nantucket, the Skipper to spend the weekend with his wife in upstate New York and me to do a round of all the

malls in the area as I had a long shopping list for things that were unavailable or prohibitively expensive in the

Azores.

As my flight home was not for a week, The Skipper and I got together again after the weekend. His partner and

two other friends had flown in from Hawaii and we all went out for a sail. It was only then that we discovered why

we had been unable to find Brenton Reef Light – it is no longer there! Sailing through the flat waters of

Narragansett Bay, I really got to understand the phrase "leaving other boats standing". Sailing at fifteen knots as

smoothly as if we were on rails (although we still had one reef in, as the mast had not yet been fixed) every other

sailboat seemed as if at anchor.

So – what of my ride with the racing fraternity? It was a thrill; it was a learning experience; it was exciting; it was

uncomfortable. Would I do it again? Not unless I get another telephone call.

[top] [voyaging page] [home]

[The following article originally appeared in "Multihulls" magazine and is reproduced with permission]