Chapter 1

Oborea’s Log: The First Leg

June 1991 to Aug 1991

Cruising yarns are supposed to be full of near misses and close shaves, that's

what makes for exciting reading, so I'll start with our nearest miss: we are

having our café au lait and croissants for breakfast in a little café in the old

quarter of Québec City when a piece of stone fascia falls from the roof of a

building being restored across the street. It strikes the opposite sidewalk and a

shard ricochets off, zings through the open window of the bistro and flies right

between our heads before clanging into the cooler at the back of the store. I

can't believe it had anything to do with us being Anglophone because, as

always in Québec, the most rudimentary attempt to speak French always

brings a friendly response. Cruising can be hazardous.

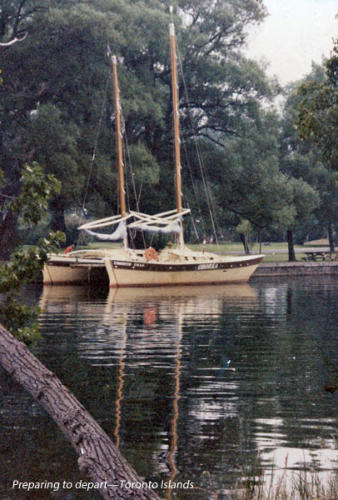

We had light but fair winds from Toronto and ran overnight to Presqu'ile Bay.

Why is it that the wind always increases at the entrance to this bay? Dropping

the spinnaker for the turn, it took a wrap around the forestay and ripped

coming down.

More light winds and much heat to Howe Island near Kingston where we

painted the Port of Registry on Oborea and had the spinnaker repaired. Then

we were on our way again, running before strong south west winds in a lot of

haze. We were through the 1,000 Islands in less than a day and did not see

much of them at all.

At Iroquois in the first Seaway lock the fall was only a few inches so they let us

right through, closing one gate behind us and opening the other ahead of us

without us having to stop (They still collected the ten dollar toll though with a

can on a pole).

At the two American locks we had tailwinds gusting to 35 knots which made

stopping interesting, but with the help of the lock attendants we made it

without incident.

We were close hauled all the way up Lake St Francis and arrived at the two

Beauharnois locks on a holiday weekend with heavy commercial and pleasure

boat traffic. It took us over three hours to get through with three power-boats

rafted to us. We spent the night at the Lord Reading Yacht Club at Beaconsfield where a friend of mine is harbour master

and on the following day we picked up another friend to sail through the last two locks and I found the only shallow spot

off the Île Dowker and went aground; we had to row out an anchor to get off, and all in front of our new friends from the

yacht club!

The last two locks were still crowded and we went through with

five other pleasure craft, a tug and a small cruise ship. We were

now, on July 1st, at sea level and spent the night at Longueil,

across the river from Montréal.

The 130 miles from Montréal to Québec City was accomplished in

two days of great heat and flat calm, motoring all the way, with an

overnight anchorage in the Nicolet River next to two tris; a Piver

and a Cross. Had one unusual experience in this part of the river:

we were motoring along when we heard the strains of Oh Canada

wafting down from above us. Part of Joe Clark's national unity

campaign? We looked up and far above us on the steep wooded

cliff was a house with a gazebo and in it a telescope on a tripod

and a pair of massive speakers. Above the gazebo the Canadian

flag was being dipped to us in salute from a high white flagpole.

At Québec City we stopped at the Vieux-Port marina and this would be a good place for some notes on marinas in Québec.

"Yacht Clubs'' here tend to be commercial enterprises with no reciprocal arrangements and marinas are more expensive

than in Ontario, but there can be a great difference in what you get for your money. At Longueil we were in a sheltered

basin with excellent floating docks, but none of the other facilities had been built yet—just neat architects' renderings on

billboards and washrooms in a trailer where a flushed toilet brought yells of anguish from scalded showerers. All this for a

dollar a foot. In Québec City for the same price we got a berth right down town in the Vieux-Port, protected from the

sixteen foot tides by a lock and with excellent support facilities and just across from a farmers market.

Below Quebéc the St Lawrence really gets interesting.

A friend who has cruised these waters a number of times gave us some advice. This part of the river has a lot of islands and

shoals with strong tides (In the Travèrse St Roche the current can reach eight knots) The high mountains are on the north

side, next to the big ship channel and most yachts follow this route. Pierre however suggested we follow the south bank

where the winds are steadier, less influenced by the mountains, and the view of the mountains would be better with the

perspective of distance. We would find the prevailing winds helping us from the south west he said, and fog was rare.

We left Québec on the outgoing tide at two in the afternoon

motoring in a flat calm with rain. These conditions continued

next day and we never saw the mountains through the mist.

We felt our way through the rocky Îles de Montmagny, past

the grim buildings of the old quarantine station on Gros Île

where hundreds of Irish emigrants have their graves, never

quite making it to their promised land. That evening at low

tide we tied up to the public wharf at St-Jean-de-Port-Joli

towering twenty feet over our heads (the tides here range

sixteen to eighteen feet). Tying up called for some agility on

the rusty ladders as well as very long dock lines and springs.

The population of the town turned out in twos and threes to

peer down at us.

Next day although we started in a hazy calm, we had a pleasant breeze for a few hours which carried us under sail (for the

first time since Montréal) through the Travèrse St Roch and on toward the Îles Kamouraska. It did not last though and we

found ourselves motoring in a heavy wind-against-tide chop to an uncomfortable anchorage in the lee of the first of the

islands. The following morning as we passed the rest of the islands the fog closed right in and I set a compass course for

the next group, the Pelerins, six miles away. The currents though fooled us and we missed by half a mile (in quarter mile

visibility) and we had to do a search pattern to find them. Here we anchored surrounded by birds: herons, gulls, ducks,

guillemots and razorbills. In the afternoon it cleared a bit and we got away under sail. As we left the islands astern a seal

popped up its head to have a look at us. That night we reached the commercial port of Gros Cacouna, just past Rivière de

Loup.

We spent thirty six hours anchored at Gros Cacouna in company with six other yachts and a European ship loading lumber

as we waited out near gale force winds, but finally we got the weather we had been waiting for: clear with south west winds

(Though it was still overcast with showers and the temperature never got above nine degrees) Twenty miles astern we

could still see the Îles Pelerin that had caused us so much trouble in the fog, while ahead of us the river lay deep and wide,

no more shoals and islands. During the day we saw many belugas, and in nine and a half hours we covered fifty-five miles

to Rimouski.

Hanging over the bar at the marina at Rimouski were eight yacht club burgees, one of them the TMCC! I never did learn its

history.

Next day the fair winds continued, and for the first time since

Québec City we had a day without rain (even a little sunshine) and

we made good seventy miles. We were into the real Gaspé now with

mountains starting to tower up on our starboard side and the north

shore visible as a thin blue-grey line thirty miles to port. No more

marinas now, only little picturesque fishing villages. In failing winds

the following day we passed the 360 foot high vertical axis wind

generator on Cap Chat that had been visible for twenty miles as it

slowly rotated and the 1,400 foot cliffs of Mont-Saint-Pierre which

have concrete launching ramps for hang-gliders at the top.

The scenery was to get even more spectacular.

The Appalachian Mountains start in Alabama and run north east

across half a continent to tumble in a series of jagged cliffs into the gulf. Nearby is Bonaventure Island where we sailed

close under cliffs where thousands of seabirds nest in noisy confusion. It was like a scene from National Geographic.

Gannets wheeled about us in the air while thousands more (dubbed by Iris 'cliff potatoes') grumbled and jostled for space

on every inch of ledge. Through it all razorbills whirred by like little penguin-rockets with their webbed feet trailing astern.

We crossed the Baie de Chaleurs, spotting a number of big whales on the

way, from the rocky coast of Québec to the low sandy shores of New

Brunswick, taking a short cut through Shippegan Gully inside Miscou and

Shippegan Islands; a four foot deep winding channel through mud flats

and out into Northumberland Strait. We had planned an overnight

passage to Charlottetown but dawn found us drifting becalmed off the

west coast of Prince Edward Island. A fishing boat out of Miminegash

dropped by for a chat: “We ain't fishing today, we's just out to get

ourselves a feed''.

An hour later they were back and tossed four freshly caught and cooked

lobsters across to us. We eventually put in to the fishing harbour of West

Point, P.E.I. where they were holding lobster boat races. Half a dozen of

these craft charging toward you at full throttle with bow waves streaming

and stacks smoking is quite a spectacle. Next day we sailed on to

Charlottetown past low red cliffs, green picture-book farms and

startlingly white lighthouses and up the Hillsborough river to anchor off the Charlottetown Yacht Club. Ashore we strolled

past gaily painted frame houses and visited Confederation Hall where Canada became a country.

Again we planned an overnight passage, this time to the Straits of Canso, and again we encountered calms and fog patches

and eventually put into Havre Boucher just short of the Strait. The strait is crossed by a causeway with a swing bridge and

tidal lock. We had heard on the radio that the current heatwave was causing the swing bridge to jam because of expansion

and the local fire department was being called in to hose it down, but things had cooled down by the time we got there and

we spent a rainy day at Port Hawksbury. Ahead of us was the Atlantic Coast of Nova Scotia, notorious for rocks, reefs and

fog. We felt our way across Chedabucto Bay (in fog) observed by dozens of seals and into the rock encumbered harbour of

Canso.

We had one hundred and fifty miles to go against the prevailing southwesterlies to Halifax, and for the first couple of days

we did not make too much progress. On the second night we sailed through Liscomb harbour where the scent of pine trees

filled the air and anchored in landlocked Spanish Ship Bay. Here one of the residents out fishing with his son dropped off

five fresh mackerel for us. The following day we were forecast twenty four hours of easterlies and we decided to go for it,

non-stop to Halifax and once out to sea, clear of all the inshore dangers we had the finest sail of the trip to date: hot

sunshine, sparkling spray, seals playing around us and a crystal clear view of the coast seven miles to starboard. We even

passed a Heavenly Twins catamaran close hauled for the Bras d'Or lakes. The splendid conditions lasted until about two in

the morning when the visibility suddenly dropped to about 100 feet in dense fog. The next couple of hours were a little

tense as we homed in on a whistle buoy. These buoys, known locally as groaners are a godsend to those of us without radar

as their sick-cow moans carry for five miles or more in good weather. The buoy finally became visible just off our bow, and

from then on it was a matter of sailing compass courses from buoy to buoy, each light coming into view just off our bows,

and disappearing almost immediately astern, trying to keep outside the shipping channels while around us just darkness

and fog and the hoots of ships and fog horns. We crept through the outer entrance of Halifax harbour and anchored off the

beach at McNab's Island to wait for daylight.

The next day brought low clouds and rain but moderate visibility and as we sailed across the shipping channel the

schooner Bluenose II crossed our bow heeling sharply to a full press of sail. We carried on up the Northwest Arm and

moored at the Armdale Yacht Club, 1400 miles in 44 days from Toronto.