TAKING it "by and large," as the sailors say, we had a pleasant ten

days' run from New York to the Azores islands—not a fast run, for the

stance is only twenty-four hundred miles—but a right pleasant one, in

the main. True, we had head winds all the time, and several stormy

experiences which sent fifty per cent. of the passengers to bed, sick, and

made the ship look dismal and deserted—stormy experiences that all

will remember who weathered them on the tumbling deck, and caught

the vast sheets of spray that every now and then sprang high in air from

the weather bow and swept the ship like a thunder shower; but for the

most part we had balmy summer weather, and nights that were even

finer than the days. We had the phenomenon of a full moon located just

in the same spot in the heavens at the same hour every night. The

reason of this singular conduct on the part of the moon did not occur to

us at first, but it did afterward when we reflected that we were gaining

about twenty minutes every day, because we were going east so

fast—we gained just about enough every day to keep along with the

moon. It was becoming an old moon to the friends we had left behind

us, but to us Joshuas it stood still in the same place, and remained

always the same.

Young Mr. Blucher, who is from the Far West, and is on his first

voyage, was a good deal worried by the constantly changing "ship

time." He was proud of his new watch at first, and used to drag it out

promptly when eight bells struck at noon, but he came to look after a

while as if he were losing confidence in it. Seven days out from New

York he came on deck, and said with great decision:

"This thing's a swindle!"

"What's a swindle?"

"Why, this watch. I bought her out in Illinois—gave $150 for her—and

I thought she was good. And, by George, she is good on shore, but

somehow she don't keep up her lick here on the water—gets seasick,

maybe. She skips; she runs along regular enough till half-past eleven,

and then, all of a sudden, she lets down. I've set that old regulator up

faster and faster, till I've shoved it clear around, but it don't do any

good; she just distances every watch in the ship, and clatters along in a

way that's astonishing till it is noon, but them eight bells always gets in

about ten minutes ahead of her, anyway. I don't know what to do with

her now. She's doing all she can—she's going her best gait, but it won't

save her. Now, don't you know, there ain't a watch on the ship that's

making better time than she is; But what does it signify? When you hear

them bells you'll find her just about ten minutes short of her score,

sure."

The ship was gaining a full hour every three days, this fellow was

trying to make his watch go fast to keep up to her. But, as he had said,

he had pushed the regulator up as far as it would go, and the watch was

"on its best gait," and so nothing was left him but to fold his hands and

see the ship beat the race. We sent him to the captain, and he explained

to him the mystery of "ship time" and set his troubled mind at rest. This

young man asked a great many questions about seasickness before we

left, and wanted to know what its characteristics were, and how he was

to tell when he had it. He found out.

We saw the usual sharks, blackfish, porpoises, etc., of course, and by

and by large schools of Portuguese men-of-war were added to the

regular list of sea wonders. Some of them were white and of a

brilliant carmine color. The nautilus is nothing but a transparent web

of jelly, that spreads to catch the wind, and has fleshy-looking

strings a foot or two long dangling from it to keep it steady in the

water. It is an accomplished sailor, and has good sailor judgment. It

reefs its sail when a storm threatens or the wind blows pretty hard,

and furls it entirely and goes down when a gale blows. Ordinarily it

keeps its sail wet and in good sailing order by turning over and

dipping it in the water for a moment. Seamen say the nautilus is only

found in these waters between the 35th and 45th parallels of latitude.

At three o'clock on the morning of the 21st of June we were

awakened and notified that the Azores islands were in sight. I said I

did not take any interest in islands at three o'clock in the morning.

But another persecutor came, and then another and another, and

finally believing that the general enthusiasm would permit no one to

slumber in peace, I got up and went sleepily on deck. It was five and

a half o'clock now, and a raw, blustering morning. The passengers

were huddled about the smoke stacks and fortified behind

ventilators, and all were wrapped in wintry costumes, and looking

sleepy and unhappy in the pitiless gale and the drenching spray.

The island in sight was Flores. It seemed only a mountain of mud

standing up out of the dull mists of the sea. But as we bore down

upon it, the sun came out and made it a beautiful picture—a mass of

green farms and meadows that swelled up to a height of fifteen

hundred feet, and mingled its upper outlines with the clouds. It was

ribbed with sharp, steep ridges, and cloven with narrow cañons, and

here and there on the heights, rocky upheavals shaped themselves

into mimic battlements and castles; and out of rifted clouds came

broad shafts of sunlight, that painted summit and slope and glen

with bands of fire, and left belts of somber shade between. It was the

aurora borealis of the frozen pole exiled to a summer land!

We skirted around two-thirds of the island, four miles from shore,

and all the opera-glasses in the ship were called into requisition to

settle disputes as to whether mossy spots on the uplands were groves

of trees or groves of weeds, or whether the white villages down by

the sea were really villages or only the clustering tombstones of

cemeteries. Finally, we stood to sea and bore away for San Miguel,

and Flores shortly became a dome of mud again, and sank down

among the mists and disappeared. But to many a seasick passenger it

was good to see the green hills again, and all were more cheerful

after this episode than anybody could have expected them to be,

considering how sinfully early they had gotten up.

But we had to change our purpose about San Miguel, for a storm

came up about noon that so tossed and pitched the vessel that

common sense dictated a run for shelter. Therefore we steered for

the nearest island of the group—Fayal (the people there pronounce it

Fy-all, and put the accent on the first syllable). We anchored in the

open roadstead of Horta, half a mile from the shore. The town has

eight thousand to ten thousand inhabitants. Its snow white houses

nestle cosily in a sea of fresh green vegetation, and no village could

look prettier or more attractive. It sits in the lap of an amphitheater

of hills which are three hundred to seven hundred feet high, and

carefully cultivated clear to their summits - not a foot of soil left

idle. Every farm and every acre is cut up into little square inclosures

by stone walls, whose duty it is to protect the growing products from

the destructive gales that blow there. These hundreds of green

squares, marked by their black lava walls, make the hills look like

vast checker-boards.

The islands belong to Portugal, and everything in Fayal has

Portuguese characteristics about it. But more of that anon. A swarm

of swarthy, noisy, lying, shoulder-shrugging, gesticulating

Portuguese boatmen, with brass rings in their ears, and fraud in their

hearts, climbed the ship's sides, and various parties of us contracted

with them to take us ashore at so much a head, silver coin of any

country. We landed under the walls of a little fort, armed with

batteries of twelve and thirty-two pounders, which Horta considered

a most formidable institution, but if we were ever to get after it with

one of our turreted monitors, they would have to move it out in the

country if they wanted it where they could go and find it again when

from

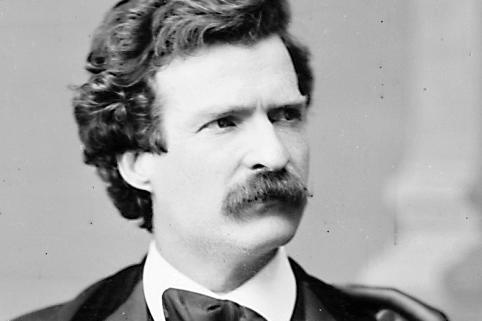

THE INNOCENTS ABROAD

by Mark Twain

1869

[continue]